“a flight pattern, a ritual, a trace”: A Review of “Séance of the Bees” by Andrea Rexilius

by Chris McCreary

“Each speech act is an act of divination,” declares Andrea Rexilius in the essayistic “She Who Hems from Source: An Introduction.” Appearing early in the collection Séance of the Bees, “She Who Hems…” serves to foreground Rexilius’s interest in the stitch “as metaphor, the near and far touching, tentatively. A temporary outpouring of relationship.” As Séance moves between nonfiction prose, poetry, and visual collage, Rexilius places “unlike things in association” in order to explore concepts of selfhood and collective identity within the context of a natural world that buzzes and hums.

In “As Long as the Stitch will Hold,” another of the collection’s incantatory prose pieces, Rexilius suggests that “(a)ll language, but perhaps especially poetic language, contains a front stitch and a back stitch. The wound and its utterance.” One wound that is central to Séance is the loss of her sister, who tragically passed away in 2017. Recounting their extraordinary first meeting elsewhere in the collection, Rexilius writes: “My father waits until I’m home to announce that he has remarried and that I have a new sibling, a 10-year-old girl from Hungary, also named Andrea.” In this moment, the young Rexilius experiences an annihilation of self - “I can’t help but feel utterly replaced, written over, erased” - and yet, she concludes, “This is the moment I become a poet”: over time, she and her sister (“part doppelganger, part mirror-image”) develop a means of communication beyond traditional speech, creating “a language of electricity, a volta, sutured (...) together with this light.” Throughout Séance, Rexilius continually seeks a way to “resentence the sentence my sister and I had been handed. To change the story by telling our story. To enter a wound.”

While the text-based portions of Séance ground Rexilius’s descent into “the realm of Persephone,” it is in the interplay of language and collage that her abiding interest in interconnection is on particularly satisfying display. Her stitching is, at times, even made literal: for instance, in the collage Lady Death, a paper doll’s outfit and the black-and-white image of animal skull resting atop its neckline are both threaded into place against a swatch of fabric, all of which is contained within the frame of an embroidery hoop.

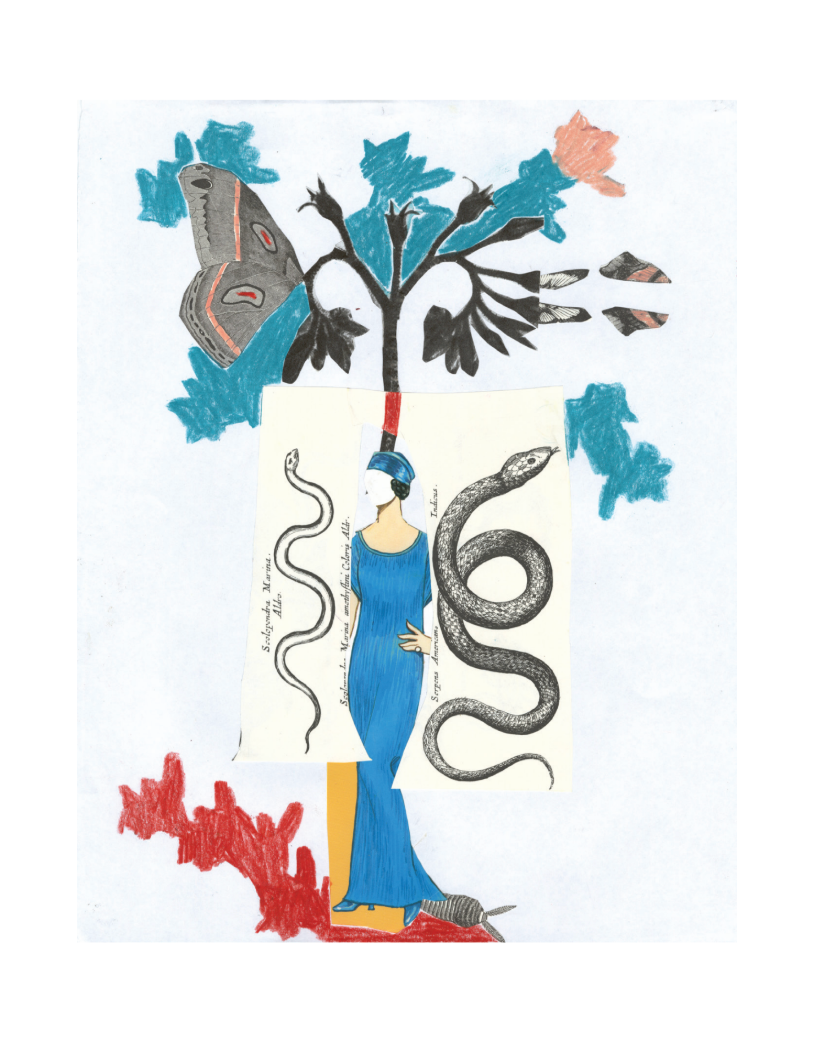

Adjacency and interconnectedness can occur on a structural level within Séance as well: the presentation of a collaged image on the verso side of a two-page spread at times illuminates concepts from the text on the right-hand side. For instance, the collage Serpens American presents an image of a faceless woman in a blue gown surrounded by antiquated illustrations of snakes and butterfly wings as well as some sketched-in foliage; the poem on the facing page, “The Structure of a Flower: Sepal,” meanwhile, describes a “Terrain of human and nonhuman elements,” the resonance “between brooks, between / branches inside a letter.” Indeed, the collage shows branches literally emerging from the top of the woman’s head, making visible for the reader the flowering of consciousness within this world of letters and images.

In Séance’s final piece, “Gluing Parts of Different Aphids Together,” Rexilius shares that the poems in the collection were written by her “past selves” between 1999 and 2024 and had been ”filed away in folders labeled ‘scraps.’” These “selves,” to my mind, are an essential part of the “multitude” of voices that surely includes her sister, her partner, and her artistic forebearers ranging from Anni Albers to Cecilia Vicuña, from the Puritans to the Dadaists and beyond. It is this multiplicity of form and voice that provides Séance, ultimately, with its coherence. By emulating the circuitous yet purposeful flight path of the bee, Rexilius joins past and present, self and other, human to flora and fauna; by seeking not to “decode or decipher but to create a cacophony,” her work truly embodies a polyvocal “woven tongue of one.”